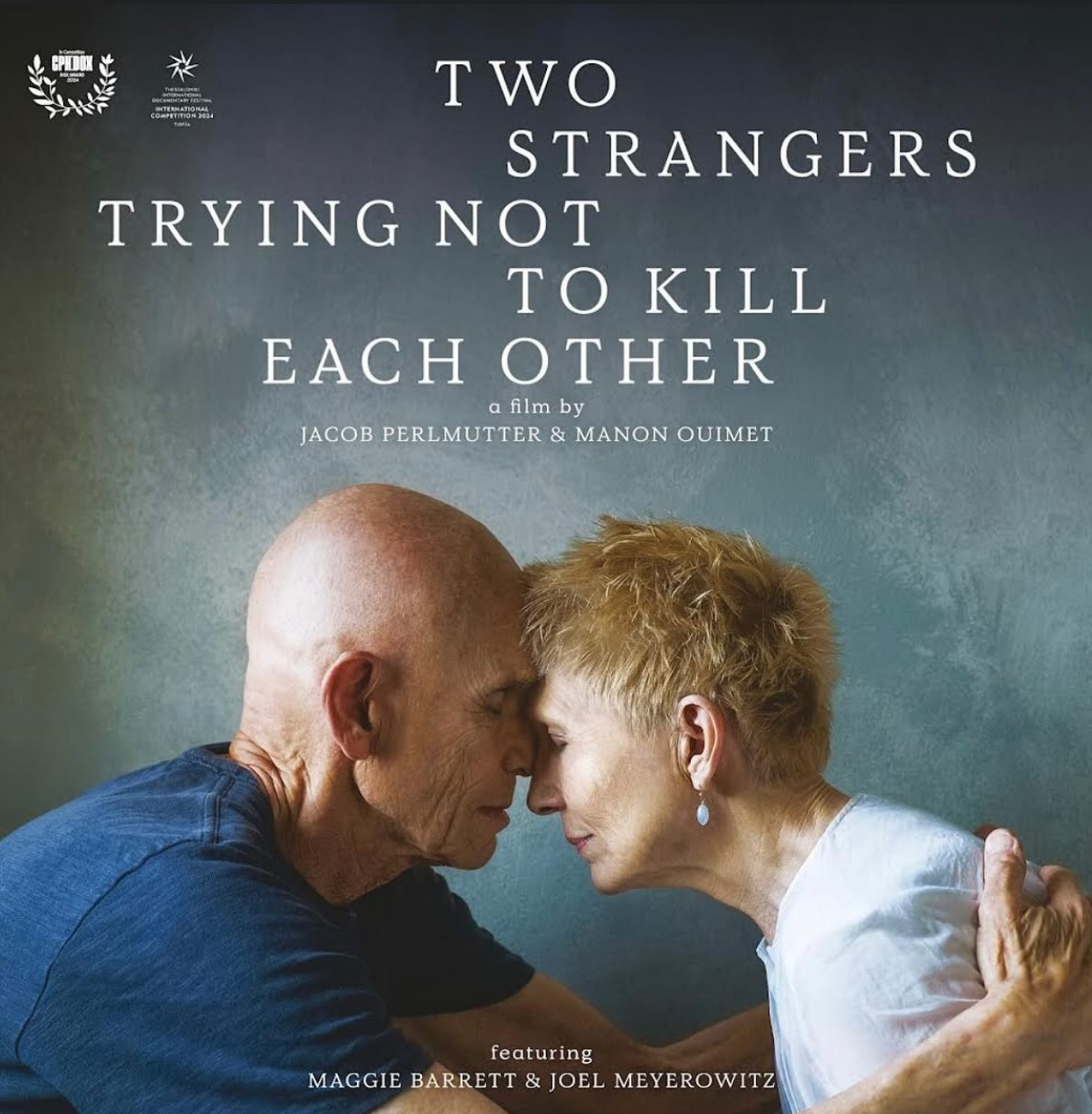

After years of being considered mostly the wife of well-acclaimed legendary photographer Joel Meyerowitz, Maggie Barrett finally gets a shout-out as an independent, equally-talented artist. It’s all because of Two Strangers Trying Not To Kill Each Other, a documentary directed by Jacob Perlmutter and Manon Ouimet. The movie shows an extraordinary and complex relationship between Maggie and Joel, both talented artists but not both equally valued. It touches on the issue of love, art, success, transience and death – creating one great piece of art, both in terms of visuality and message. The movie was the hit of Polish festival Millennium Docs Against Gravity. It was also awarded at the Philadelphia Film Festival and Copenhagen International Documentary Festival.

Writer, painter, poet, ex-dancer, pianist – it’s difficult to find a ground of art that Barrett didn’t do. Artistic expression seems to be a medicine to her tough experiences. Her life was the story of finding herself. She coped with multiple abuses, drug and alcohol addictions, child loss, failed marriages and many more. Hard to believe it all happened to one person… Now 78-year-old, Barrett speaks openly about her past. It is quite an important thread of her artworks. Barrett’s art – paintings, drawings, poems, essays and many more – can be tracked on her personal blog, www.maggiebarrett.com. What is her attitude towards life? Is she happy now? What is art to her? In a conversation with Maks Wieczorski, Maggie Barrett tries to find the answer to those and many more questions.

Movie about you and your husband, Two Strangers Trying Not To Kill Each Other, recently premiered in the UK at the London Film Festival and then a couple of days ago it was shortlisted for Best Documentary at the British Independent Film Awards. That’s a huge thing, so we have to start with that. How was this idea about making a film about you and Joel born?

It’s actually quite a long story, which happened mostly in Tuscany. I’m now speaking to you from London, but back then we were living in Tuscany, where we actually lived for ten years. Once Joel had gone out to do some grocery shopping, and Jacob Perlmutter [the co-director of Two Strangers Trying Not To Kill Each Other] saw and followed him because he wanted to say hi. When he got into the shop, Joel had disappeared. He must have gone in and out through another aisle.

So they didn’t meet?

No, they didn’t. Jacob went home to Manon [Manon Ouimet is co-director of the movie and partner to Jacob] and was, you know, really upset that he’d missed meeting his hero.

But that’s not how the story ended…

A few weeks later, Jacob saw both of us on the street and stopped us. That wasn’t something new because Joel is being stopped on the street quite often. In most of those conversations nobody’s in the least bit interested in me. Joel is their hero, so it’s all about him. I just stand there or walk away. But Jacob was different. He was engaged with both of us.

I still vaguely remembered that conversation until around September 2021 when I got an email from Jacob, who evidently had found me on Instagram and then had found my blog. He started reading all my essays and realized that I was a fairly interesting person, too. These are his words, not mine…

So what did he write in that email?

He said that we had some kind of aura as a couple that he found fascinating. That at our ages – Joel, in his eighties, me in my seventies – we still gave off this kind of youthful energy and we were really still in love. He thought that would be an interesting story that you don’t see very often. There are only few love stories about older people and certainly about two artists.

So he just offered to make this movie?

He asked if we were into it. I told Joel about it and we all met on Zoom. Then at Christmas, just a couple of months later, Jacob and Manon came down to Tuscany. And that’s how the adventure began…

The effect of that adventure is a truly amazing movie which really shows you and Joel both as people and artists. It doesn’t depict you as the wife of an artist, it shows you as an independent, great, amazing personality. That’s so important in the culture of reducing wives of artists to just being a wife.

That’s lovely what you say. One of the things that was really wonderful for me about making the film with Jacob and Manon was that I did feel truly seen by them. You know, after thirty odd years of being with Joel, and very often not being seen because of his fame, to be seen as an equal by these two young people was a really wonderful sort of validation of who I am. Actually it was also an interesting mirroring in that Jacob and Manon are a younger version of us in a way, although they’re starting off much more equal in terms of, obviously, success.

On the screen we can see you showing off your really intimate, sometimes difficult emotions.

Well, they’re not very pretty emotions either.

Yeah. It’s about the frustration of being unseen living with a person who is indeed extremely seen. Those are difficult emotions.

We had two Zooms with Jacob and Manon before they came to Tuscany. Once I said to them, ‘look, it’s very nice to make a love story about an older artist couple, but honestly, if you’re going to do this, we have to show – there’s the saying in English – the warts as well. We have to show it ain’t perfect.’ The commitment is to love, and love is what sustains the relationship, but there’s shit that comes up.

Not many people are brave enough to talk about it, to be honest. And not only about those feelings. You talked openly about all the tough things you went through in your life.

As an artist I have to try to be all about honesty and authenticity. Many people meet me, see the person that I’m now and assume that I’ve always been that person. And I haven’t been this person, as you can tell from the film. Drugs, alcohol, all kinds of shit. But I think that showing that is worth it. Because if I show you that I came from this and now I am this, then there’s hope for you too. People are looking for perfection – and of course, in public we show those perfect sides of ourselves. On the street, Joel and I look like this perfect older couple who were always in love and it’s all cool – it’s not. I always wanted the film to show all of it.

So were there any moments you hesitated to show off something on the screen?

It was written into the contract that we would see the film before it went public. So I have to say that, although I didn’t have any problem in the moment of making the film, I had one doubt while watching it. Do you remember the scene, where I basically, as we say in English, rip Joel another asshole?

Yeah. The great argument scene. One of the heaviest ones.

That’s right. When I saw that on the screen, I thought it was absolutely vital, but I also did wonder what I was letting myself in for. I assumed that a lot of men watching that would have a problem with it. And what was interesting, is that in all the screenings that we’ve had, it’s the men who have come up to me in tears afterwards.

Why do you think it is so?

My theory is that when men watch that scene, they recognize their patriarchal selves in it. But, because then it’s not actually about them, they’re able to stand back and see themselves not having to defend themselves. The editor of the film told me that every time he got to that scene he would yell out at Joel on the screen. I think that’s like one of the little gifts of the film.

The power of cinema… You can move other people and make them think a little bit differently.

It’s a beautiful feeling, isn’t it?

It certainly is. There is another scene that I found moving. The scene in which you destroy your diaries. Memories that you were writing down for a great part of your life. First of all – did you really destroy them or was it just imitation?

No, it was all true and totally from me. We had gone back to New York at that time, because we were in the process of getting our apartment ready to sell. So I was going through cupboards and drawers and looked at these two shelves of my journals from when I was in my twenties. At that moment I thought, ‘where the hell am I going to put all those journals in our new flat’?. Then I asked myself, what do they really mean to me, what value do they have in my life right now. I realized that they had already served their purpose in my life.

Was it tough for you to destroy them?

You have to know that those were not pretty memories. Those were all years of me searching for myself. All the questioning, all the yearning, all the failures, all the hard stuff, basically. There were some beautiful poems here and there in those journals but I thought – ‘really, am I going to sit down and read them again one day’? The answer was ‘no’.

The thing is that in that scene you metaphorically broke with the past, all the terrible things that happened to you.

That is right. I had lived it. Why would I want to live all that shit again? And also, the other concern for me was, when I die, who looks at those journals? Do my children look at them? I certainly wouldn’t want my daughter to look at them. I wouldn’t want her to look at that stuff. Again, those were books of heartache, yearning, failure and trying to write my way, understand what I was doing in my life. Also, I accepted at some point in my life that, unlike Joel, I was not going to be a famous person. So my archive was completely irrelevant.

What did you feel when you destroyed those journals?

When I was tearing the pages out, I was in tears. It was painful. Every once in a while, I would catch sight of a sentence and start to read and literally stop myself, because it was painful to sit with years of struggle. Which, in a way, validated the reason for getting rid of it. It was wrenching because I poured a lot of energy into all those journals. And then the actual burning of the pages and literally seeing it all go off in smoke was liberating.

The form of therapy… wasn’t it?

Absolutely.

On your blog I found the quote, ‘At a certain point, the only hope for progress is acceptance. And it’s a bitch’. That’s somehow what you did with your journals. You just accepted your past, although it was painful.

Exactly! I really appreciate that it ended up in this movie.

Do you consider art some form of therapy?

I do think that art is therapeutic, but I don’t think it always helps.

What do you mean?

It depends on what we mean by help. I’m going to make a very crass example. Picasso, one of the greatest artists ever. Was his art therapeutic to him? No, I don’t think so. He didn’t have a choice. He was a great artist, he had to do it – but it didn’t evolve him as a human being. He wasn’t really a very charming human being.

Yeah. That’s true…

So, I think it’s a tricky thing with art in terms of it being therapeutic. What I personally find therapeutic about making art is that I feel like I disappear. I’m not involved with myself. And for those hours, whether it’s writing a novel or playing the piano, I’m lost in the process of something other than me.

So you lose control for those moments?

I have control over in terms of craft, but if you’re really open as a creative person, you let go of control to see, what can the muse tell you today. One of the things that I find therapeutic, particularly in drawing and painting, is that I feel like I’m a vessel and that something comes through me. It’s not that I’m making this thing, it’s that I’m opening up myself for something larger than me to have its voice. That almost makes me feel like I belong to the universe in a way, to an energy that’s greater than my own.

That must be an amazing feeling, isn’t it?

It’s a beautiful feeling. And then when you put the pen or brush down… You have to go back to reality. You’re like ‘Oh, shit, I got to go to the grocery store’…

Which of the arts you spoke about – poetry, writing novels, music, or maybe painting – is the closest to you?

I can’t really nail it down to one thing. For instance, painting and visual art is very close to me because it’s about being. It’s, for me, not involving the mind.

It’s about expression, right?

Pure expression and movement. I’m also an ex-dancer, so in that way I feel connected to a form of expression that doesn’t need explanation.

So you assume that visual art doesn’t need explanation.

Yes, not at all.

So what with the writing?

The value is that it’s made me very disciplined about the mind and about language. When I write essays, I very often don’t know what it is that I want the essay to be about. When I write an essay, I’m looking for the next question that I need to ask myself and find an answer to. But I’m also looking for the way in which the personal can become universal. The essay starts with me but it ends up with you.

Is it different in the case of a novel?

With novels I always have a different kind of connection. I have to think of every word and sentence. They have to lean on the next ones. Writing a novel you have to use your mind more consciously. And ask yourself some questions.

What questions?

What are you saying? What is this novel about? Who is this character about? What is their problem? What are they going to do with the problem? Are they going to resolve the problem, or is the novel going to leave it open-ended, so the reader could decide what they would do in that situation? I’m somebody who dropped out of school at the age of 15. I earned my MFA in creative writing in my forties, having never gone to college. I was the only person to be accepted into an MFA program who didn’t have a bachelor’s degree first. I didn’t even have a high school diploma. So I sort of grew up thinking of myself as being stupid and dumb. Becoming a writer gave me a sense of myself as somebody to be reckoned with. I have a mind, and it’s finely honed.

In your latest novel’s Felicity description it’s said: ‘After a lifetime of drinking, drugging, multiple marriages and several unpublished novels, Felicity finds herself living in a foreign country with husband number five. Now sober, seventy, feisty and furious, she is on a mission to discover where her anger comes from and how dissipate it while she still has time’. Reading that, one can have the impression that Felicity is a character similar to you. Is it kind of autobiographical?

I would call it autofiction, although I actually hate the term. People who know me kept saying that I should write a memoir and I’ve always been resistant to it for a couple of reasons.

What reasons?

One is that I find the memoir a form that is somewhat self-indulgent and quite humorless. The other reason is that I felt that my story would, quite frankly, not be easy to believe in. I mean… somebody may have been raped, and somebody else may have been adopted, and somebody else maybe lost a child, maybe somebody else has been married five times. But very few people have had all of those things happen. So I never gave a thought to writing a memoir.

So, if I see the point well, you just packed your experiences into a fictional character?

You know, one day in Tuscany, when I was driving home from the grocery shopping, I literally had a vision of this other woman called Felicity. She was enraged. And I asked myself, what she’s so pissed off about. Then I gave her much of my life. Because when I give it to somebody else to live, I can make it a work of art instead of a memoir.

You already talked about it – your life wasn’t an easy one… Saying ‘not easy’ is actually like saying nothing. But at this point of your life, do you still have in you the anger of Felicity?

Yes, I do still have this anger in me and I had it for most of my life. Although it was different in different phases of my life. When I was an alcoholic, I was quite proud of my anger. It was a way for a woman to assert herself. And I think that many women get confused between aggression and assertion.

So that was the anger you developed as a defense mechanism?

Yeah, I certainly wasn’t an angry person when I was younger. Usually, anger is covering up another emotion that is more uncomfortable to feel. The anger is also something bigger, socially.

What do you mean?

I think that women – I’m speaking generally here – particularly in this day and age, are quite angry at men. They are pissed off at the history of the patriarchy. You say it once in a gentle voice and you’re not heard. Then you say it again a bit louder. Still not heard. Then you are angry and shout out loud. And then you’re blamed for being angry. Same in very particular cases. I have gone through a period where I have judged myself for being angry and felt ashamed about it.

Has it changed?

Now I accept my rage. I’m a human being, and it’s okay. I take it rather as a clue that I need to have a conversation about something. I’m not somebody who holds a grudge. I do move on emotionally quite quickly. But it required years of learning.

Speaking of your attitude towards life, do you think that you are now at the happiest point?

I’m certainly at the most grateful point. I think that we in western culture live under a lot of misconceptions about happiness. It is thought that when you do enough work on ourselves, everything will be okay and we’ll never again have an unhappy day. Happiness to me is about accepting that there will be ups and downs.

In the poem Hourglass from 1997 you wrote ‘Yesterday/I don’t know. It went./Today the traffic is dangerous. Trees are appealing, but the sea?/All tides out and the sand/ is dry, dry, dry.’. That’s the exact idea of acceptance.

Absolutely. There are going to be both great and dark days. That’s just part of who you are. I have so much gratitude for all that I have. I look at my life and all I came through and I think: ‘wow, what I became’. I’m incredibly grateful to Joel. I’m surrounded by friends. I have a great relationship with my daughter now after years of struggle. So, yes, in the larger sense, this is most certainly the happiest period of my life. That said, it really sucks that we have to die.

Death is something that’s quite resistant to this acceptance…

Somebody asked Woody Allen once, ‘what do you think about death?’. He said, ‘I’m not into it’. When you’ve had a long life and half of it was really hard, and then the second half was all about taking responsibility for your own life and evolving and finally coming to the place where you are happy – you want this half to last. Yeah, it’s hard that Joel is 86 and I’m 78. We know that death is much nearer. That’s the hardest thing, probably.

What would you say to your 18-year-old self? With all that wisdom about life you gained through the years, with all you came through.

I would say – have faith that you will find yourself and belong to yourself…

Maks Wieczorski